Pharmacist -2

Siegfried Letzel

Hahnemann,

the Pharmacist -2

We already met Hahnemann as one of the first important chemists in a previous article. This wasn’t the only scientific field in which he proved to be a pioneer. He began incorporating new discoveries from chemistry into medicine on numerous occasions. Initially, this primarily concerned medications.

In 1787, he co-authored the book “The Characteristics of the Quality and Adulteration of Medicines” with the Brussels pharmacist van den Sande . The chemical part and the components of the drugs are from Hahnemann’s pen. Hahnemann presents the “proving substances” for the medicines in a concise, concise, and exhaustive manner, similar to those found in modern pharmacopoeias (official pharmacopoeias).

Even back then, Hahnemann was already lamenting the “unreliability of pharmaceutical preparations” and asking: “What can the doctor rely on?” Pharmacists mixed their prescriptions differently, and the quality of the raw materials was very mixed. As a result, patients ultimately had no way of knowing what medicine they were actually taking. Hahnemann’s precision and unconditional attention to detail allowed him to gain new insights. He called for a regulated method of manufacturing medicines: “… so that we may finally, in the healing arts, obtain a reliable standard for the powers of this remedy .” He wrote this when calling for the production of tartar emetic (potassium antimonyl tartrate) – a medicine used as an emetic at the time.

At that time, chemists were also searching for a mercury preparation for treating (mostly syphilitic) patients that would be less caustic and toxic than the usual preparation. Hahnemann discovered a process for producing Mercurius solubilis (much later, this substance was given the additional name ‘Hahnemanni’). This medicine was considerably more tolerable than the previous one. One critic stated: “Art owes one of the most effective, mild mercurial preparations to the famous and therefore immortal Hahnemann . “

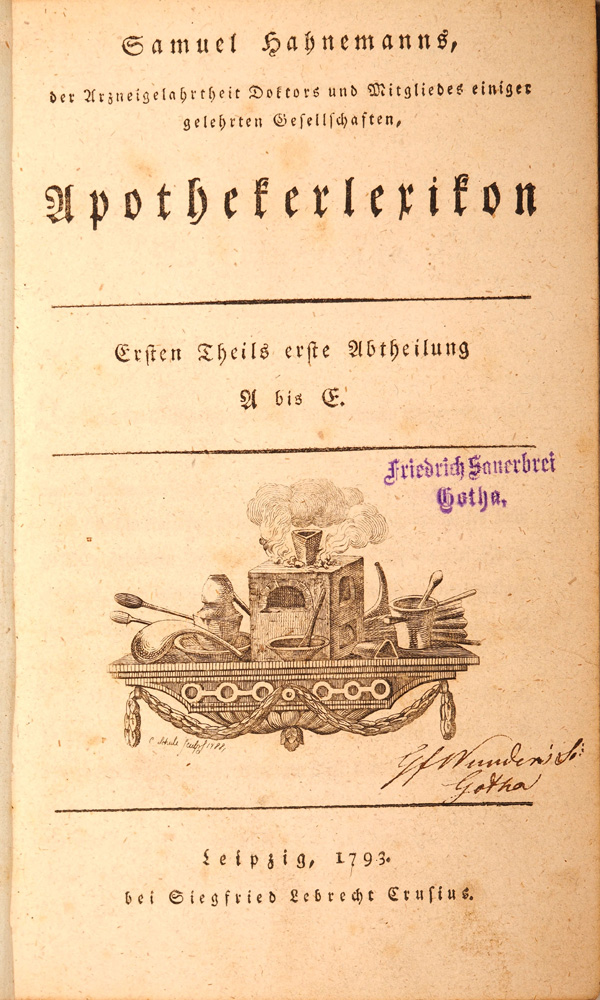

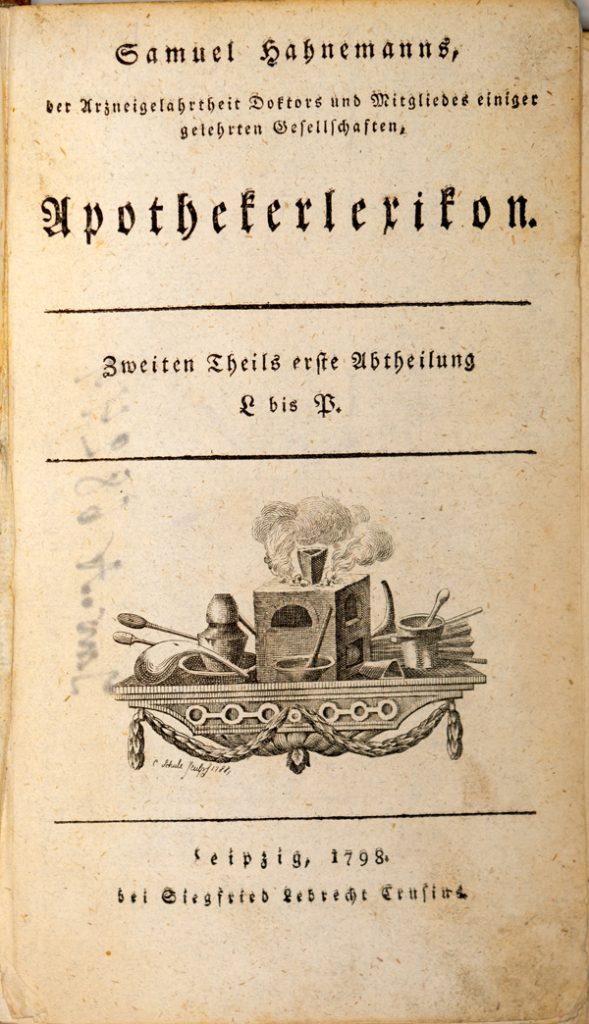

In 1793 and 1799, the two volumes of his four-part ‘Apothecary’s Encyclopedia’ (over 1,200 pages) were published, a very comprehensive work. “The material is arranged alphabetically and discusses all subjects of interest to the pharmacist in his work. The presentation is concise, lively, and stimulating. One finds a precise description of the most practical arrangement of a pharmacy and its rooms. Likewise, the individual utensils are described precisely and with great expert knowledge. Each of these articles demonstrates Hahnemann’s intimate knowledge of the work. He frequently cites new apparatuses he invented or improved, not without supporting understanding with illustrations.” This is how a book review from 1884 put it.

For the first time, pharmacists received very precise instructions for all aspects of their professional activities. This also applied to their work in their laboratories and with prescriptions, with many instructions even becoming legal regulations. Hahnemann demonstrated his expertise even in seemingly insignificant matters, for he was a practical man and familiar with the problems and difficulties faced by pharmacists. Thus, it was not a big step for a number of Hahnemann’s recommendations, which he included in his lexicon, to be generally accepted for pharmacy management.

Kraus’s ‘Medicinal Lexicon’ states: “Hahnemann is a recognized expert pharmacist and, as such, earned unfading laurels through his presentation of his so-called Mercurius solubilis and, in part, through his treatise on arsenic poisoning, although this theory was significantly improved immediately after his death.”

Thus, the Torgau native’s spirit of inquiry and iron diligence made important contributions, both directly and indirectly, to the improvement of medical healing tools, as they were then called. He contributed significantly to improving the quality and reliability of medications, one of the foundations of medical art.

The Pharmacists’ Encyclopedia is a true masterpiece. When our society acquired an otherwise out-of-print copy of the reprint years ago, we were stunned by the breadth of the work. It’s no wonder, then, that it received worthy attention for a good 100 years, despite the rapid advances in science. Even today, some of Hahnemann’s principles and contributions are considered self-evident.

Both volumes, with their four parts from 1793 to 1799, are now in our collection in their original form. We are delighted that these extremely rare books are now easily accessible to visitors to our exhibition. And this is one of our association’s goals: safeguarding and preserving the works of this world-famous physician!