Chemist

Siegfried Letzel

Hahnemann,

the Chemist

Why is there still so much hype today about Samuel Hahnemann, who passed away in 1843? To get a sense of his scientific achievements, we must consider the worldview of the ‘educated’ people of his time. Hahnemann’s contribution to the emergence of modern chemistry is a good example of this.

Scientists of the 18th and 19th centuries still lacked all the fundamental knowledge in their fields and had yet to develop the first steps toward breaking away from medieval ideas and creating rational knowledge. The emerging era of Enlightenment came at a great time for scholars like Hahnemann. Now it was time to move away from superstition and toward creating one’s own knowledge—using one’s own reason!

In chemistry, the teachings of Joh. Joach. Becher (1636-1682) and G. E. Stahl (1660-1734) were still valid, and thus the theory of phlogiston. According to Prof. Neumann, this was the combustible principle without which nothing in the world can burn. Sulfur therefore consisted of sulfuric acid and phlogiston. Wood was ash plus phlogiston (when wood burned, the phlogiston escaped and ash remained). Water was “nothing but a transparent earth, liquefied by heat, which was called ice. It consists of four elements: terra vitrescens, terra mercurialis, terra sulfurea, and terra inflammibilis.” And Neumann was an absolute authority in Hahnemann’s time!

So, at that time, people were still searching for the “basic essence” of bodies, the elements.

Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier finally put an end to the old “ruminations” against fierce resistance. According to him, water did not transform into earth, but consisted of hydrogen and oxygen. He showed that the oxidation process of metals was the ‘swallowing’ of oxygen.

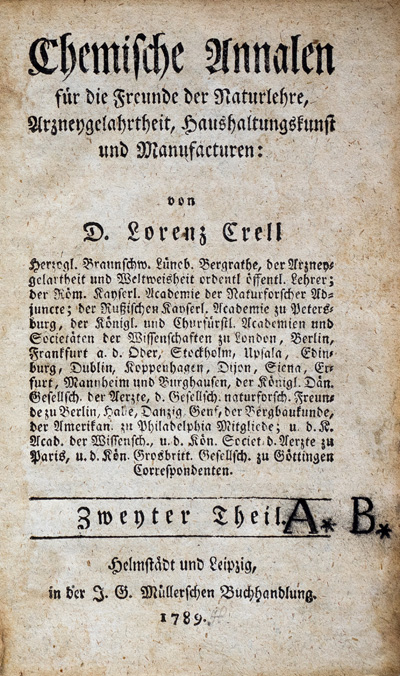

At this time, Hahnemann published articles in Crell’s Chemischen Annalen. These covered, for example, the influence of certain types of air on wine fermentation, wine tastings of adulterated wine for iron and lead, methods of preparing soluble mercury, and much more.

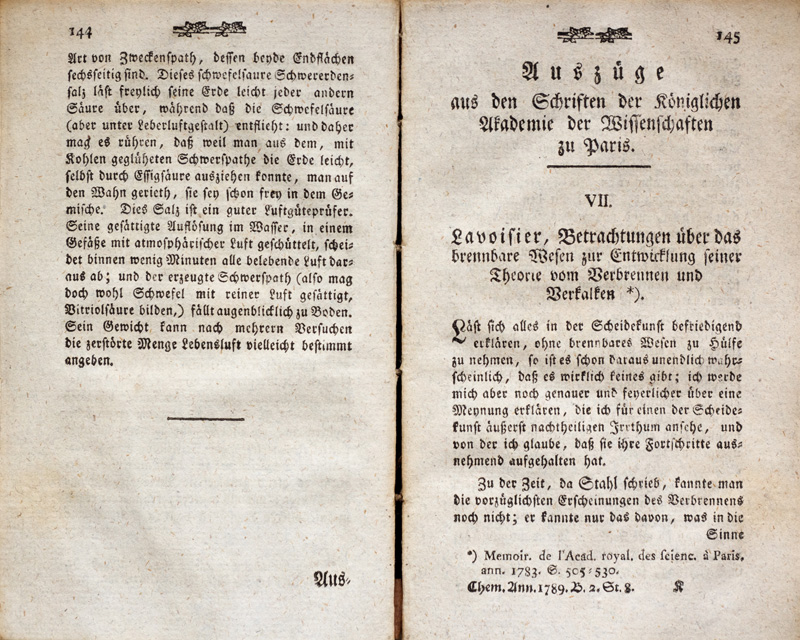

Hahnemann wanted to conduct research with Lavoisier to reach a decision on the question of phlogiston. Unfortunately, this never happened due to the outbreak of the French Revolution, during which Lavoisier was guillotined (1794). It was not until 1799 that Lavoisier was recognized by most ‘artists of separation.’ By this time, Hahnemann was already much further ahead.

In chemistry, Hahnemann was necessarily self-taught. In 1784, he translated two volumes of Demachy’s work on the industrial manufacture of chemical products into German. He significantly improved this work with his annotations. Demachy was a member of the scientific academies in Paris and Berlin. Hahnemann demonstrated astonishing knowledge of all aspects of the book. His extensive knowledge of the literature, which he applied to better understand the original work, is evident. He often explained chemical processes in more detail or corrected errors and mistakes.

In 1786, Hahnemann published the book “On Arsenic Poisoning, Its Relief and Judicial Remedies .” According to the physician Bergrath Dr. Buchholtz in Weimar, this classic work contained “the best arsenic analyses ever introduced into forensic medicine.”

Here, Hahnemann was already among the first pioneers to contribute to the utilization of the latest knowledge of chemistry in medicine. And he did this very successfully, as we will see in our next article.

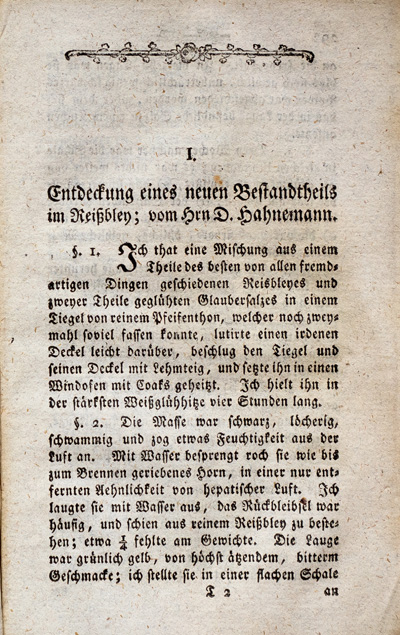

Our exhibition features a rare gem from that time. It is a 1789 edition of Crell’s Chemical Annals. Hahnemann wrote two articles in it, the more detailed one on “The Discovery of a New Constituent in Lead” (Graphite). Immediately before Hahnemann’s work is one by Antoine Lavoisier: “Reflections on Combustible Materials for the Development of the Theory of Combustion and Calcification .” Who would now doubt that Dr. Samuel Hahnemann was not among the world’s most renowned chemists of his time? And with that, he was still very much at the beginning of his scientific studies…