Cholera Epidemic

Siegfried Letzel

Hahnemann in the face of the cholera epidemic of 1831

The year 2020 will likely go down in history as the ‘coronavirus crisis’ – less from a medical perspective than from an economic one. Given all the restrictions and sacrifices that society at large had to make to ensure medical care for the population with a sufficient number of intensive care beds and ventilators, one might well ask what comparable scenarios would have been like back then, when scientific medicine in the form we know it today did not yet exist.

Epidemics and pandemics, infectious diseases in general, have always existed in human history. Bacteria and viruses were not yet known – not even hygiene, as we take it for granted today. Primarily in urban areas and especially during ‘bad’ times and times of war, infectious diseases, both acute and chronic, were constant companions of human life.

At times when epidemics were rampant, people were quite hopelessly exposed to them. Doctors tried to help their patients with all possible therapeutic methods, but the death rate was often unbearably high.

This was also the case in 1831, when a murderous epidemic, originating in Russia, swept across Europe with incredible speed and lethality (approximately 200,000 victims). The Baltic states, Poland (1,100 deaths in Warsaw alone), and Galicia were already affected. In Prussia and Austria, the borders were closed. Quarantine stations were set up. Nevertheless, this Asian cholera could not be stopped.

In their ignorance, the doctors were helpless. Bloodletting was a very common treatment method; leeches and cupping were used, as were medicines such as calomel (a poisonous mercury preparation). This medicine was the essential standard emetic and laxative at the time and was found in virtually every doctor’s bag. As you can see, most therapeutic attempts further weakened the patients, which was not particularly beneficial. A ‘Pharmacopoea anticholerica’ (a pharmacopoeia of remedies for cholera) contained 238 drug descriptions, all of which, by today’s standards, were ineffective.

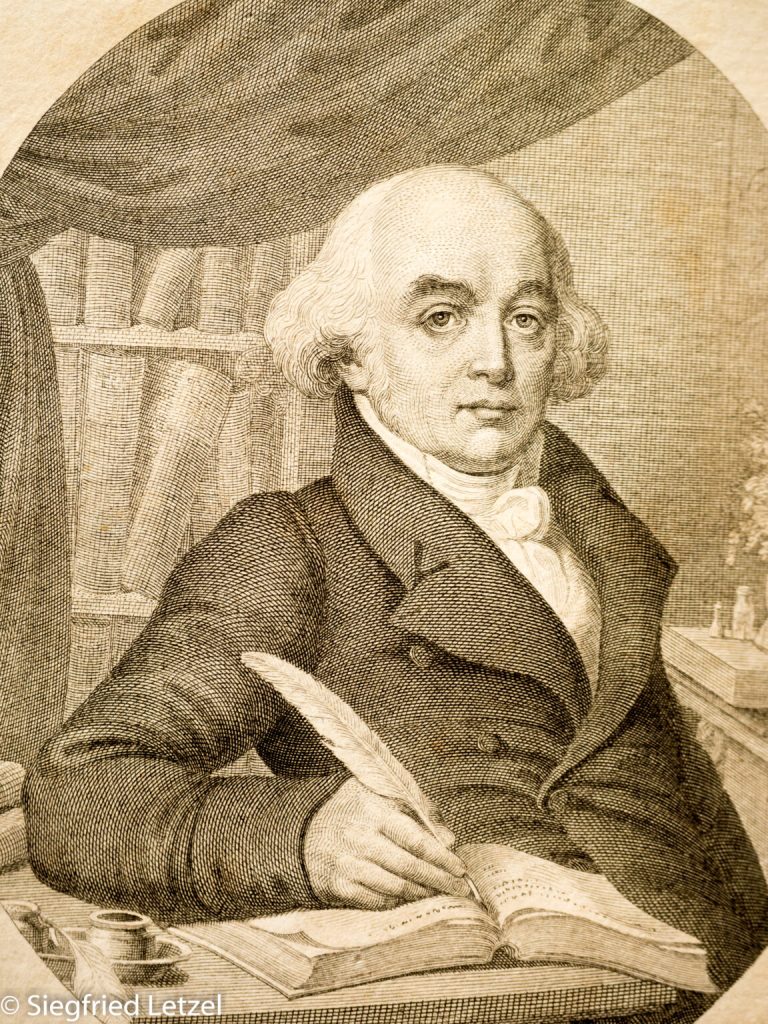

At this time of agony and hopelessness, it was the Meissen-born chemist, pharmacologist, and physician Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, founder of homeopathy, who published his own therapeutic approach in four works.

Even at that time, he suspected that so-called choleramiasma existed “in a living being of a homicidal nature that escapes our understanding.” According to philosopher Fechner’s study of 54 researchers, Samuel Hahnemann was the only one who assumed microorganisms and came close to the cause of the disease.

Hahnemann remained true to his now-adopted principle of treating cholera as an ‘established disease’ by administering the same remedy to all patients. With his ‘Therapia Magna Sterilisans’, he was the first physician to recommend camphor spirit as a medicinal remedy—but also as a protective and disinfectant—for use against the threat of cholera.

In advanced stages of the disease, he recommended homeopathic remedies appropriate to the symptoms.

In this, he was alone in his approach. The treatment recommended by Hahnemann soon proved to be extraordinarily valuable and successful. Even medical authorities were reluctant to recommend his method.

But Hahnemann thought even further to prevent further infections and spread: he demanded that all persons in quarantine or who come into contact there “expose their laundry, etc., to oven heat of 80 degrees for two hours. This is a heat in which all known infectious agents, including living miasmas, are destroyed. During this time, their bodies are cleansed by rapid washing and provided with clean, linen or fustian [thick cotton] clothing appropriate to the home.”

This was simply revolutionary in Western medicine.

Considering that Hahnemann had neither microscopy at his disposal to the extent that it does in modern science, nor was it possible to personally observe cholera patients (in Köthen), so that he was solely dependent on the detailed descriptions of the disease and symptoms of his friends and students, whom he had expressly and urgently requested, it is truly astonishing with what certainty and confidence he, perhaps the first, pointed to choleramiasma as a “living being of a lower order, which, in its smallness, is removed from our natural senses.” Then, based on this insight, he firmly asserted and maintained the contagious nature of the disease, which was spread through personal contact. This understanding also led to his antidotes, which were so remarkably effective for the conditions of the time.

The cholera epidemic of 1831 led to a rapid increase in the acceptance of homeopathy, which is still practiced worldwide and essentially unchanged to this day.