Happiness

Siegfried Letzel

Temporary happiness found

Torgau. We find ourselves in a deserted, cobblestone alley. On both sides, the Gothic-style houses stand side by side. Most are quite old, two-story gabled houses. Their windows are closed. The smell of smoke, cow, pig, horse, and chicken manure wafts around us, sometimes stronger, sometimes weaker, wherever we are. The smoke from the chimneys gives the houses an appearance that makes anyone who isn’t already accustomed to it from a longer stay feel melancholy. The streets are empty, even though we’re close to the city center. Only occasionally do we meet someone. People greet us friendly as they hurry past us, heading toward their destination. It’s cold, and it’s winter.

It’s December, and New Year’s Day is barely a week away. The year is 1804. Although the city is quite large and spread out, it has fewer than 6,000 inhabitants. The city is almost entirely surrounded by the waters of the Elbe River… Suddenly, the sound of horses’ hooves on the pavement and the clatter of carriages and carts break the silence.

A small procession comes up the alley and stops in front of one of the larger houses. Although it was built in the old town, it was still one of the oldest buildings in the area. The location seems perfect: it’s just a few steps from the church, castle, and town hall. The history of the property dates back to 1447, and it is known as the “Electoral Free House.” Documents show that there must have been a house here even before the catastrophic city fire of 1442. It’s easy to imagine that this property was already very old and historic in 1804.

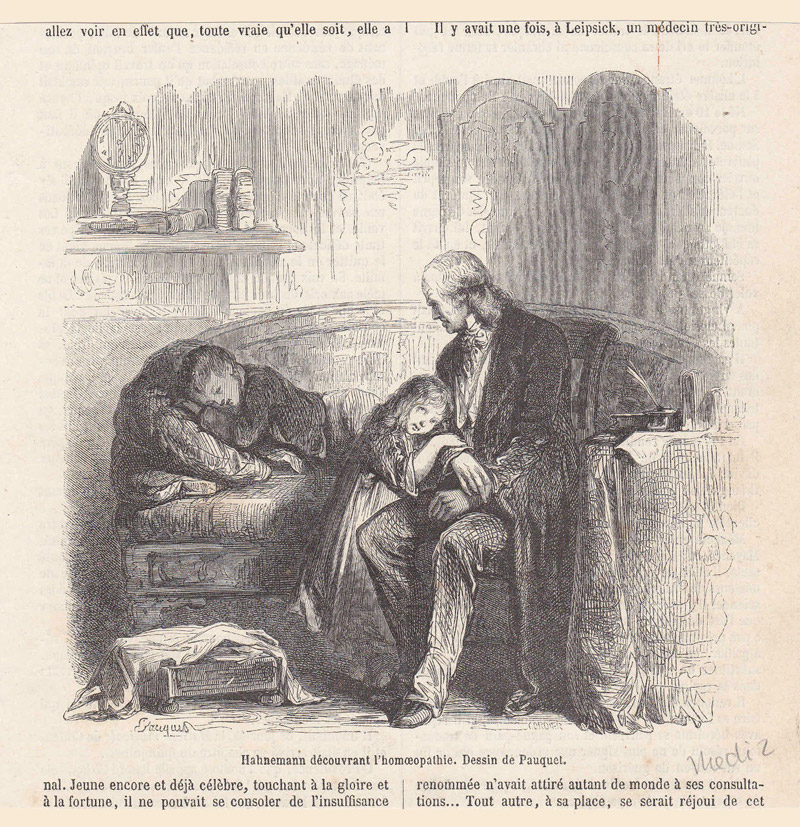

In front of the house, we see a 50-year-old aristocratic gentleman, along with a few helpers. Next to him is his 41-year-old wife and seven children between the ages of 5 and 21. The head of the family is Dr. Samuel Hahnemann, the new owner of the house. He was of a gaunt build, and it was obvious that he hadn’t been raised on fertile land. He was a sinewy, perfectly healthy man. Although his outward appearance was small and frail, it immediately revealed—in his bearing on the street and within his own home, towards visitors and patients—the unusual dignity and outstanding worth of his personality.

He will use three rooms and four closets in his new home for his family; one living room and one closet (totaling 60 m²) will be used for his medical practice. His family’s living space is sufficient for life in cramped conditions.

Hahnemann spent what were arguably the happiest and most creative years of his life in his house in Torgau. His family welcomed two more children in 1805 and 1806. He always felt most at home with his family and displayed his most endearing inclination toward cheerfulness and joy. He joked with his children in the time he could devote to them, sang lullabies to the little ones, and composed songs for them. However, the family in Torgau also suffered a severe blow: in 1807, their 16-year-old daughter, Karoline, died.

In 1811, Dr. Hahnemann and his family left the city again. The main reason was the ever-increasing threat of war. Torgau was expanded into a fortress. The cityscape changed completely with the construction of new ramparts. City walls and gates were demolished, along with many houses and two churches. Now enemies could no longer approach the city unseen. The fortress surrounded the city with several ramparts, entrenchments, walls, and barracks. Dr. Hahnemann knew he could no longer guarantee his family’s safety. And he was right: In 1813, the city of Torgau was struck by siege, shelling, bombardment, and epidemics. Approximately 30,000 French soldiers and 1,122 peaceful residents lost their lives.