Tireless Man

Siegfried Letzel

Hahnemann,

A tireless man

The younger Samuel Hahnemann had to pay for almost every step of his life with deprivation. These deprivations shaped a slight, sinewy, but extremely healthy man, carved from hard, durable wood. Thus, he was able to remain tirelessly active well into old age and even run a highly successful medical practice until his 88th year.

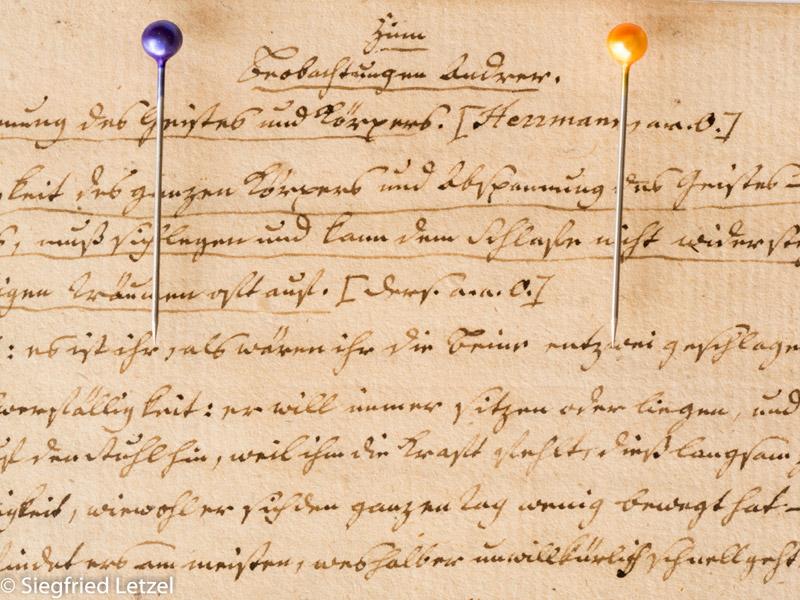

Hahnemann’s facial expression is described as captivating and enchanting. His high forehead, which had developed early on – his strands of hair now only flowed around his temples and the back of his head – underscored the physiognomy of a thinker. His eyes, sunk deep into his forehead, were bright and penetrating and never required corrective lenses. His expression showed ‘natural gentleness, but also relentless, clear seriousness, illuminated by a ray of devoted love and willingness to serve people’. He had almost womanishly delicate hands, but a distinctly masculine handwriting in its firmness, closeness, and evenness.

His frugality was evident in his choice of plain, inexpensive paper.

He filled the pages from top to bottom, never leaving any large blank spaces. His writings are neat and tidy, with rare alterations and improvements. This is a testament to his powers of concentration, combined with the sharpness and clarity of his thoughts and his complete mastery of and penetration of the material he was writing about.

Lines are closely spaced, each one running perfectly straight across the sheet of paper.

Due to the roughness of the paper and the small size of his writing, he could only use unsplit quills. It seems he only switched to steel pens in 1833.

We house an extremely rare manuscript by Hahnemann with scientific text – the likes of which are almost never offered on the antiques market.

This sheet shown here measures 17.5 x 21.5 cm. The font size can be estimated from the pins next to the heading. And so Hahnemann wrote many thousands of pages.

The two pages managed by the Hahnemann Center come from the manuscript for the 6th volume of his Pure Materia Medica, 2nd edition, which he wrote between 1822 and 1827. Incidentally, the manuscript pages for the remedies Wütherich and Zinn were considered lost. This one by Zinn is the only one whose whereabouts are known. This alone attests to the historical value of this document

Back to Hahnemann: He was also frugal with physical pleasures. Even during his prosperous years, he allowed himself thin, sweet beer and his pipe. He rarely drank wine, coffee, or tea. Otherwise, he seemed to keep himself young through his work. He once wrote: “Late in the evening, one goes to bed dead tired, and after a short sleep, one rises in the morning fresh and strengthened for new work.”

The English physician Dr. Dudgeon once wrote: “We can only begin to get a true idea of his industriousness when we realize that he tested approximately 100 different remedies, that he wrote nearly 70 original works on chemistry and medicine, several of which comprise several substantial volumes, and that he translated 24 works, some of them multi-volume, from English, French, Italian, and Latin, dealing with chemistry, pharmacology, agriculture, and general literature. And all this alongside his medical practice and his work as a teacher!”

Dudgeon had no insight into the numerous and impressive volumes of Hahnemann’s medical journals and repertories, nor into the still-incalculable number of patient letters that arrived at his door, all of which he read, annotating them with a brief summary of his responses and answering them in detail.

Hahnemann was a rare master of his native language, which corresponds to the style of classical German literature. In his old age, Hahnemann’s language became more ponderous and pompous. Typical were the extraordinarily long sentences with frequent interpolation and explanatory insertions. His sentence structures were complicated, confusing, and difficult to understand. Except in his letters: they were written in grammar and easy and fluent to read.